Growth Insights| November 2024

CMO Blueprint: The path to creating an effective annual plan

Almost every marketer has faced the fallout of a bad annual plan – whether it was reactive, or based on false assumptions, or simply impossible to execute. Fortunately, we get plenty of chances to iterate – annual planning comes back around every year.

At a recent workshop with marketing leaders across Spectrum’s portfolio, Kurt Apen, CMO of Spectrum portfolio company Otter.ai was joined by Jason Lyman, CMO of portfolio company Customer.io, and Spectrum Equity’s own CFO Brian Regan and CMO Dan Kimball.

These experienced operators – who have seen both good and objectively bad annual planning – had plenty to share with their marketing peers.

Panelists clockwise from top left: Otter.ai CMO Kurt Apen; Customer.io CMO Jason Lyman; Spectrum CMO Dan Kimball; Spectrum CFO Brian Regan

Guiding principles of results-driven annual planning

The group kicked off with a set of shared philosophies around annual planning. Use these principles – the result of plenty of trial and error – to approach your annual planning in the right frame of mind.

-

Great marketing leaders are great investors. CMOs should think about themselves as portfolio managers who uniquely understand how to allocate resources across the highest priority initiative. This ownership mindset can also preempt friction between Marketing and Finance, drawing a clearer line between activities and impact.

-

You can’t plan what you don’t understand. Before kicking off an annual plan, leaders should clearly understand – and contribute to – their organization’s long-term strategic and financial goals. Only from there can you back into Marketing-specific plans. “Marketing leaders can be the torch holders here,” says Spectrum CMO Dan Kimball. “We can be the ones who zoom out and ask, ‘What are we really trying to achieve?’

-

Annual planning is a “full cycle” process. Annual planning is sometimes limited to an (often painstaking) period of documentation that ends once budget and headcount are allocated. Instead, allow annual planning to be a continuous, cyclical process, which looks something like this:

- Review, discuss, decide, and document your plan with OKRs nested beneath each goal

- Communicate your plan

- Execute your plan

- Monitor your execution

- Return to step 1 – On a quarterly basis, use your OKRs to review what you’ve accomplished, surface learnings, and decide on your team’s next moves.

Assessing your annual plan: Criteria for results-driven planning

Spectrum CFO Brian Regan has been part of many planning cycles at both private and public companies of every size. “The best companies often include the best planners to help focus while enabling agility in execution,” says Brian. So what separates good annual plans from the bad?

Your annual plan should narrow your team’s focus. Growth companies are “opportunity rich” – a good problem to have, but also a minefield for distractions. A solid plan should explicitly limit the “side quests”, and help you justify the work your team won’t do, putting your horsepower behind the most impactful activities.

As Kurt Apen puts it, “The ability to focus on what not to do is just as important as deciding what to pursue. Too often, marketing teams spread themselves thin, attempting to execute on too many initiatives, which dilutes the overall impact.”

Your annual plan should build alignment – across all of your stakeholders, including your employees, your management team, and your board members. Level-set on the type of plan you create, the appropriate confidence intervals, and how aggressive your plan will be – allowing you to surface and resolve existing misalignments.

“You need to understand where to expect key drivers of growth – whether it’s from existing customers, expansion, retention, net new acquisition,” agrees Kurt. “If you have that model, you can focus on impact from the get-go: Here’s where marketing is going to plug in.”

Your annual plan should be measurable and achievable. As you map out goals, your partners in finance should help you assign metrics – and help you understand what is realistically measurable.

“Your CFO should be helping you identify the most relevant metrics, define and establish achievable objectives for your team, and determine if your goals can be reliably measured with clean and consistent data hygiene,” says Brian. “They should also help ‘operationalize’ and communicate the specific initiatives in terms of cross-functional team alignment and accountability.”

Your annual plan should have a Plan B. And C. “One thing is certain: actual results are never going to happen exactly as you planned,” says Brian. As part of your planning process, you should also be anticipating difficult conversations throughout the year, in terms of key tradeoffs, re-prioritization, and alternative scenarios to your original plans. Ideally, quarterly re-forecasting is baked into your cycle. The best leaders identify upside and downside scenarios upfront, and understand how quickly their company can react to shifting market or competitive conditions.

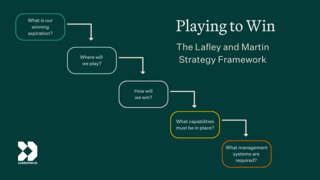

How Customer.io Plans: The “Play to Win” Framework

At Customer.io, Jason Lyman’s team relies on the “Play to Win” framework – a structured approach to annual planning, which is outlined in AJ Lafley and George Martin’s best-selling book of the same name.

“As a marketing leader, you need to translate the way your plans support the larger company efforts,” says Jason. “That generally means you need a set of materials you can point to, that represent the core of the plan you’re delivering. I’ve used the Play to Win framework at a number of companies, because it leaves you with just that – a set of deliverables you can refer your stakeholders to.”

Step 1: Decide on your “Winning aspiration.” In this step, company leadership should set a bold, audacious goal for the business – ultimately, its purpose. These goals should be set at the company level, leaving you to ask: “What does this mean for me as a marketing leader?”

Step 2: Decide where to “play.” With your North Star aspiration to guide you, you need to find the right playing field – whether it’s in terms of geographies, product categories, consumer segments, channels, or verticals. To do this, Jason recommends identifying your Ideal Customer Profile (ICP), so you can avoid spreading your team too thin with activities that won’t deliver the results you want.

Step 3. Decide how you’ll “win.” Jason generally advises marketing leaders to focus on 3-5 strategic areas that will drive the most value. These should be backed by primary or secondary research to ensure they are tied to broader business outcomes.

Step 4: Determine which “capabilities” you’ll need. In this framework, your “capabilities” are essentially your activities, and the way you do them – this is the step where you’ll translate strategic goals into specific actions. “You don’t want to have a grand strategy that no one knows how to put into practice,” says Jason. “This is where you build in the tactical commitments.”

Step 5: Determine which “management systems” you’ll use. This last step is about systems for execution – figuring out how to operationalize everything you’ve built into your plan so far. “For example, I’m personally a big fan of OKR frameworks because they build clear accountability around activities,” says Jason.

As Jason notes, marketing leaders may pick and choose which steps work best for their business and level of organizational sophistication. “If I could leave marketing leaders with a central takeaway, I’d say that annual plans should always have a goal, 3-5 focus areas, activities and tactics to support those areas, a budget and headcount plan, and a scorecard of metrics you can use to assess performance,” says Jason.

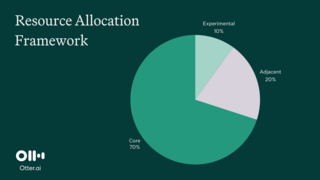

How Otter.ai balances their investments: Resource allocation framework

Once you’ve aligned on strategy, you enter one of the trickiest phases of annual planning: resource allocation. This stage generally maps to steps 3 and 4 above – deciding which strategic areas are most important, and determining how you’ll execute against them.

At Otter.ai, Kurt and his team use a tried-and-true framework to balance their approach. Developed during his time at eBay, this framework helps him lead his team to the right breakdown of investments: core work, adjacent work, and experimental work.

“An example of core would be your main business – initiatives that you have high confidence in, execution-wise, and know will contribute to your goals,” says Kurt. “An adjacency might be an upcoming expansion into a new language market or launching a new product – areas that might not be part of your core plan this year, but will eventually be part of your core business.”

The last piece, experimentation, often falls out of your plan – often because to invest in it, you need buy-in from your CEO and CFO.

“Experimentation and learning are really important today, given how quickly channels change and develop,” says Kurt. “As a marketing leader, you need to get that buy-in, that you’re going to spend 10% of your budget and time and resources to try new things.”

A 10% allocation isn’t a hard and fast rule – the important thing is to surface and align on risk tolerance, so you come to a baseline allocation everyone has agreed to. “Your CFO or CEO may come back to you and say that the company doesn’t have tolerance for experimental work,” says Kurt. “But that’s an opportunity for you to open up the conversation. You need to invest in those adjacencies and experiments today for the sake of your future growth.”

Once you’ve aligned on these buckets, you’ll have an important way to contextualize your plans. While your CFO might have looked at your planned activities as a list of expenses to cut – with unproven, higher-risk plans first on the chopping block – you can now tie it back to the allocation model: “If you’ve agreed that a percentage of your work should be experimental, and you’ve acknowledged that the initiative falls into that bucket, you’re having a totally different conversation,” says Kurt.

Common annual planning mistakes – and how to avoid them

No marketing plan is perfect, but we can – hopefully – avoid repeating our mistakes. The leaders shared their own “teachable moments” from their marketing careers:

Mistake #1: Setting unrealistic expectations. “This is the difference between a marketing leader with great marketing maturity and one who is less mature,” says Dan Kimball. “The annual planning process is an opportunity for you to look at a plan and say: ‘I can only achieve this if, for example, we have this specific resource.’ Or ‘I can’t achieve this’ – whether it’s due to external market factors or internal capabilities. Mature marketing leaders will have that hard conversation, and ultimately your CEO will appreciate it.”

Mistake #2: Making decisions sequentially, rather than simultaneously. To Jason, the key to good strategy is making interconnected choices between teams. “At a previous company, my team got really excited about a particular product, and we did a great job of building out an experience that we thought would be successful,” Jason recalls. “But we didn’t adequately resource the GTM (go-to-market) during our annual planning – we assumed we’d figure it out once the product was ready.” Because they hadn’t decided how to bring the product to market, there was a disconnect – and the product never got the traction it deserved.

Mistake #3: Allowing the SUV to roll downhill (aka inertia). As you think about what your team did last year, there’s often an implicit expectation that they’ll do the same things again. “Annual planning is your opportunity to ask the serious question: Is this the most important thing? Is it still driving the outcomes we’re looking for?” says Kurt. “Where I’ve had the most difficulty with this is where it impacts the team – you’ve hired someone into a specific role, but the reality is dynamic. When you think about developing your team, you might need to re-train or re-deploy people…and annual planning is a time to figure that out.”

Final thoughts: Planning outside of silos

At the end of the day, annual “planning” is just one (very necessary) step in a larger process. To actually execute on your plan, you’ll need to drive well-orchestrated collaboration across your company – and you’ll need your counterparts to account for their own resource investments to support your marketing goals, wherever there are dependencies. For that reason, and despite the coordination it requires, annual planning is best done in concert with your counterparts – not only with your GTM partners, but also with Product, Engineering and other organizations across the business.

“When I work with marketing leaders in our portfolio, cross-functional collaboration is one of the most frequent challenges we solve for,” says Dan. "It’s not just about crafting a plan, but ensuring every part of the business has a stake in bringing it to life. Great plans happen when every leader is invested—not just in the end goal, but in the path to get there.”

The content on this site, including but not limited to blog posts, portfolio news, Spectrum news, and external coverage, is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice. Use of any information presented is at your own risk. Spectrum Equity is not responsible for any content reposted above from any third party website, and has not verified the accuracy of any third party content contained above. Spectrum Equity makes no guarantees or other representations regarding any results that may be obtained from use of this content. Investment decisions should always be made in consultation with a financial advisor and based on individual research and due diligence. Past performance is not indicative of future results, and there is a possibility of loss in connection with an investment in any Spectrum Fund. To the fullest extent permitted by law, Spectrum Equity disclaims all liability for any inaccuracies, omissions, or reliance on the information, analysis, or opinions presented.