perspectives

How SponsorUnited’s Bob Lynch Rewrote his Playbook

Like many great companies, SponsorUnited was born in a basement.

In 2014, Bob Lynch was responsible for corporate marketing partnerships – in other words, sponsorships – at the Miami Dolphins.

But even after more than a decade in sports and entertainment marketing, he found the ecosystem complex and nebulous. It was surprisingly difficult to get even basic sponsorship info on athletes, influencers, team, and events – and absolutely no way to see it all in one place.

Founded by Bob in 2016, SponsorUnited’s intelligence platform has changed the sponsorship game for brands and rights holders. With the largest single repository on sponsorship transactions in the industry, SponsorUnited has become an ‘all-day-every-day’ tool for sponsorship sellers at teams, sponsorship buyers at brands, and agents or other intermediaries in the ecosystem.

The data that Bob wished was more transparent and actionable has now become exactly that – with a comprehensive inventory on the visuals, deal details, and specifics of what is being bought and sold in this market.

And while Bob Lynch’s story is unique, it raises questions that many founders grapple with: How much risk should you tolerate? When is it time to expand your circle of trust? How do you keep evolving – in the way you run your business, but also in the way you live your life?

Spectrum’s Emily Calkins was Bob’s intro to the firm over three years ago (the two met for lunch in Stamford, CT) and helped spearhead Spectrum’s investment. The two sat down to discuss the (multiple) leaps of faith required to found a company, the challenge of growing a team and bringing on new partners, and the joys of building what you can’t buy.

Emily Calkins: Let’s start with the backstory. Where did the idea for SponsorUnited come from? And how did you realize it should become a reality?

Bob Lynch: There wasn't one moment where I had the idea. But there was a time when I felt I had a full understanding of the problem I wanted to solve.

When I first got into working for teams and sports, it was hard for me to grasp the scope of sponsorship. I was coming from the advertising industry, which at the time was very binary – there were 30-second ads and 60-second ads. This is the size of your ad, this is the scope. We could knock down a wall and call it a club, or we could do an event in the community and post about it on social. By comparison sponsorship seemed very abstract.

So the seed was planted there: I didn’t understand what other people in my field were doing, and I was struggling to understand how sponsorships were bought and sold. I also saw that I wasn’t alone on this – my peers and colleagues were struggling too. I didn’t know what the solution was, but over time I realized that I needed more access to information – that data would be really valuable to me. And then I recognized that other people would probably want that data too.

Emily: So once you found that pain point, and started to realize there might be a company there – what pushed you to actually build it?

Bob: I had thought about companies in general for a very long time – even as a kid I was pretty entrepreneurial. But I had a wife and kids and a mortgage and a pretty cool job…that made it hard to take the leap.

But I reached a point where I felt like I was just doing the same thing over and over again, like that old member of a rock band who’s just playing the hits. I think many people come upon this at some point in their life – your skill set starts to atrophy, and you slow down the pace at which you’re growing. My options for growth were limited in my field, and looking at the people who were senior to me, I didn’t necessarily envy the lives that they led every day at the arena. It was a grind.

Also my father had passed away a few years before that, so I was having thoughts like, “What’s my legacy going to be?” So I came to a kind of “business midlife crisis” – like what am I going to be for the next 20, 30 years of my life? I didn’t want to have to say, at the end of my life, that I never took the shot.

We had a newborn and a two year old, and we were living in Brooklyn. But I kept talking to my wife about it, and even though we weren’t in a position for her to say this – she told me to go figure it out. It took a lot of courage on her part to say, “Go downstairs in the basement and don’t come upstairs until you have the idea.”

I didn’t know anything about technology – I didn’t even have any experience in data. But I thought I had a novel way of capturing this information and bringing it to the market. So I said “Alright, let me just go figure this out.”

Emily: So you got that push, and you started building SponsorUnited. When did it start to hit that your idea might actually work?

Bob: It took a while. Early on, we were just working on how to get the data and information. But at one point I’d started to show mock-ups of what the platform would look like – I literally sketched it out into a PowerPoint to make it look like a website. I brought it to a mentor of mine, Jim Rushton, who’s the CCO of the Washington Commanders now but was with the Chargers at the time. And Jim said “Oh, these would be great reports. In theory, if you could do this, it would be amazing.”

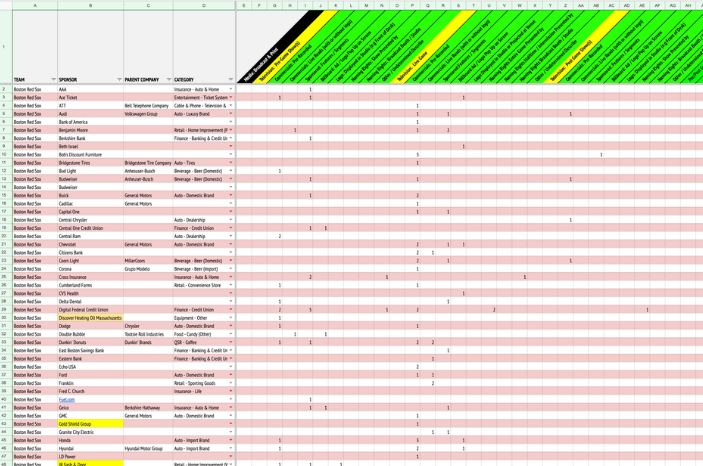

Initially we did everything in spreadsheets –

Emily: That’s the nickname “Bobby Spreadsheets!”

Bob: Yes! They were in Google Sheets! We had the LA Chargers – an NFL team – using Google Sheets to leverage this thing. And absolutely loving it. They saw value in the data there too. So when we built the actual platform and brought it to people, I could tell that they weren’t just being nice – they were actually intrigued by what we could do.

As I was trying to figure out how to actually get the data, I happened to read Peter Thiel’s book, Zero to One. He talks about how you should seek out really hard problems to solve, if solving the problem will unlock tremendous value. That gave me a lot of solace then, and it still does now.

Emily: So if those were the moments of confidence building – what about the moments when you had the most doubts? Did you ever think “I want to go back to my sponsorship job”?

Bob: The honest answer is that I always had doubts. Every day you have doubts – I still have doubts today. Every day there’s something wrong, there’s a fire to put out, an issue…The question is about when you listen to those doubts, and when you don’t. It’s like Edison’s journey – there are always thousands of failures, and every day is a failure. So how do you put it in perspective and see those failures as a good thing?

The creative and personal freedom was also such a big tradeoff – it made it so I never wanted to work for someone else again. To be honest with you, the happiest day I had was in the spring of those early days. I was making no money, paying our bills from savings, but I was able to go to lunch with my wife – just in the middle of the day on a Tuesday. I thought, “Wow, I’m happier now than when I had a huge bonus check from the NFL, and all of the stresses that came along with it.”

Emily: Tell me about your decision to bootstrap your company for as long as you did. It’s a common theme across companies Spectrum invests in – two out of three were bootstrapped when we invested – and I know that can impact a lot of decisions. How did you navigate that choice?

Bob: I almost took money right out of the gate, from a VC. At the time I thought the terms were amazing – like, I went home to my wife and said “They valued my idea at over a million dollars! This is incredible.” When I realized that it wasn’t such a great deal, it was actually a little bit deflating – I was a first-time founder with kids and a mortgage, and I was tapping into my own money to make it happen.

But it’s just like if you go to Vegas, and you say: this is my money I’m putting in, and I’m okay with losing it. I had to mentally come around to that. Also my thought was that even if the company failed and I lost money, the things I was learning were valuable to my career. Also I’d lived through it on some level – my dad almost lost it all in the 80s, and we got through.

So once I could get over the risk, it became a matter of: Do we have enough money to fund what we need? That ethos of bootstrapping. And as long as we were scrappy, the answer was yes. Originally we had to create a data infrastructure, which didn’t actually require developing technology or making a financial investment – we just had to find creative ways to get the information. Not having money to do everything actually produced great ideas. I’m sure there were also some control issues at play for me…But I felt like being bootstrapped created a discipline and a work ethic – without the crutch of money that we didn’t actually need.

Emily: I know you heard from a ton of firms like Spectrum – on the phone, coming to your kids’ sports games, courting you…How did you decide that it was time to raise money?

Bob: We were at a point in our business where for us to truly scale, we needed to have more sophistication – both in a business partner, but also to be able to invest more in the product. The next level of customers were going to be very different businesses, with different needs and challenges, that we’d need to sell into. There was a bit of an undefined roadmap when it came to solving for more complex data.

We’ve all heard the “Do things that don’t scale” advice for startups, and we did do a lot of things that didn’t scale. But we’d gotten to a point where we needed to be smarter about how our organization grew, and how we collected our data.

Emily: If you could have lunch with 36-year-old Bob, who was just embarking on this journey – or a founder of a future Spectrum company at a similar stage – what would you say to that person?

Bob: There are so many things that I look back on and think – Oh man, I wish I hadn’t done that. But it’s tricky because sometimes you have to make those mistakes and have those failures.

With that said, I’d probably rethink the talent and staffing needs from early on. Especially when you’re bootstrapped, your initial feeling is: If anybody will come with me on this journey, I’ll be happy. And coming from sports, I valued teamwork – I was focused on getting the talent to work together.

But now, if I could go back, I’d be thinking about the middle of the journey too – I might have been more proactive in seeking out different skill sets, in making sure we had the skills we needed. We probably could’ve moved more efficiently, and been able to make decisions faster.

On a more tactical note, I wish I had told people to pay their subscription fees upfront. We probably could’ve bootstrapped even longer. I’ve been kicking myself for that one.

Emily: Thinking about other founders building companies – what else do you want them to know?

Bob: I’m in Boston for our board meeting today, which is the birthplace of my business career almost a quarter century ago. I woke up this morning and I looked out at Boston, and I was thinking about how I used to prospect in the Boston Globe and rip out the little ads...in paper! To do my job! I used to write letters to people, and then do phone calls, and work through gatekeepers…and I was thinking just how much things have changed. So many skills have a half-life because the world changes around us so fast.

And so I think the challenge for founders – even if you only founded your company five years ago – is that so much has already changed since you started your business. I think of generals in World War I who were fighting with machine guns – but they were trained back at West Point with horses and rifles. So how do you continue to learn? How do you not lose who you are at your core, even as you’re approaching a totally new environment?

Going back to your question about networks – I think the best founders can do is to have as many different viewpoints as possible on where your industry is going. My kids, for example, helped me understand how the next generation is consuming content, and we were inspired by video games and the dynamics of TikTok, and EA Sports to design our platform.

The bottom line is: When you start a company you go through a massive discomfort level, and that fades as you start to have some level of success. You need to get uncomfortable again.